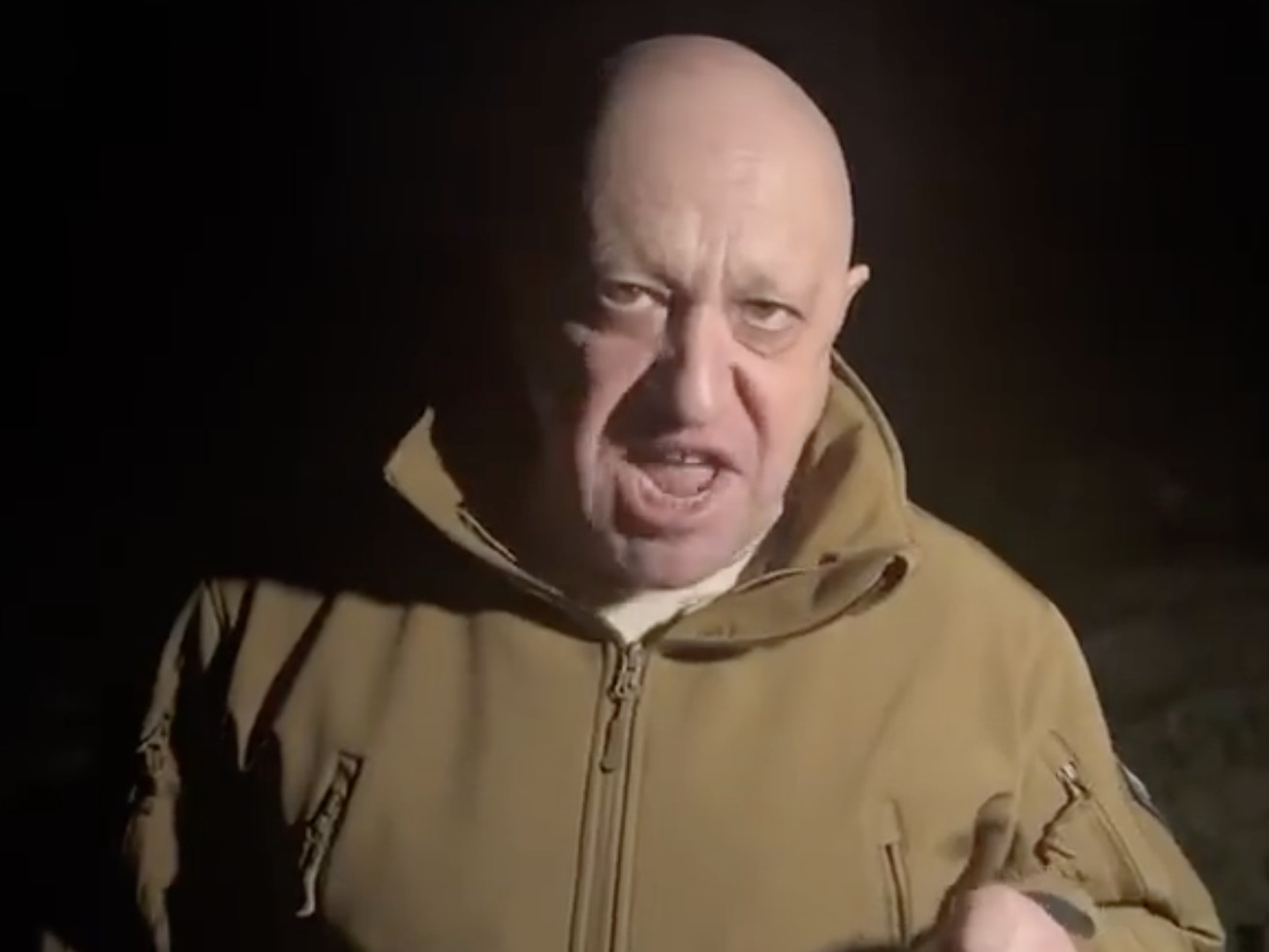

Standing in front of dead bodies, a Russian paramilitary commander curses out the country’s military brass.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of Russia’s Wagner Group paramilitary corps, is standing in front of a field of dead bodies and screaming. He rants and curses while being filmed, pointing at the corpses of his men.

As the video goes on, he gets angrier and angrier, specifically blaming the deaths of his men on Russia’s two highest ranking military officials — Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov. According to Prigozhin, those two leaders denied Wagner fighters the artillery ammunition they needed to defend themselves.

“Shoigu! Gerasimov! Where are the fucking shells!” Prigozhin says. “They came here as volunteers and died so you could gorge yourselves in your offices.” (You can watch the video here, but be warned — it’s graphic.)

So here you have a Russian paramilitary leader publicly advertising his high casualties in gruesome form and, even worse, publicly cursing out the top of the command chain for their deaths. And this isn’t even the first time he’s done something like this. It’s a kind of insubordination and dissent that, in a properly functioning military, simply shouldn’t happen.

But at this point in the Ukraine war, we know that the Russian military is very much not functioning properly. And Prigozhin’s video, for all its horrific spectacle, actually helps us understand an important reason why — Russia’s military is divided against itself by design.

It’s a set-up created to help Putin stay in power. But it’s also one that is likely damaging the country’s ability to perform on the battlefield.

How Putin’s authoritarianism hurt his military

In theory, the Wagner Group is a kind of mercenary outfit. In practice, as my colleague Jen Kirby explains, it’s more like a privatized arm of the Russian state — often deployed to help pro-Russian dictators in places like Syria where it’s more useful to have them than regular Russian army troops.

During the Ukraine war, Wagner has functioned much more like a branch of the Russian military. Wagner fighters are currently taking the lead in the offensive against Bakhmut, a city that has emerged as the central front in the past few months of fighting. Experts say that Prigozhin’s forces have been generally well supplied by the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD); his grievances about ammunition in the above video seem to reflect this support slacking off.

“Wagner has long had a significant artillery advantage in Bakhmut and received preferential support,” writes Rob Lee, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute who studies the Russian military. “This [video] is likely a reflection of the MoD rationing ammunition before Ukraine’s counteroffensive. The MoD has to defend the whole front but Prigozhin only cares about taking Bakhmut.”

That, according to Lee, reflects a serious problem for the Russian military. Militaries perform best when there’s “unity of command,” meaning a clear structure of authority where everyone follows the orders given to them by their specific higher-ups. When you have divisions in the leadership class, it hampers your ability to pursue objectives as a united armed force. There’s no better sign that Russia is failing in this regard than its leaders feuding publicly — even using dead Russian soldiers as props in their PR battle.

So why are the Russian armed forces divided among themselves, split into various different units with different command structures? Part of the story, in the specific case of Wagner, is that it can be useful to have a paramilitary force that can operate in the shadows. But more generally, setting up his military this way helps Putin prevents a coup.

To pull off a military coup, the plotters need to have significant amounts of authority over the bulk of the armed forces to ensure that they will take the right actions at the right time. To prevent this, dictators engage in a series of behaviors that political scientists call “coup-proofing.”

One key tactic is dividing up the military command structure — separating out the regular army from the national guard from the armed wings of various intelligence agencies from paramilitary groups like Wagner. That way, no military or intelligence leader can be sure that they will have the united loyalty of the full armed forces if they attempt to depose the leader.

Putin has extensively split up Russia’s armed forces for exactly this reason, and it seems to have worked pretty well for him as a matter of staving off coups. Even this current feuding between Prigozhin and others, experts say, is not likely a sign of instability in the Russian regime.

“Cracks within elites are not necessarily a sign of Putin weakening if it makes him even more important as the ultimate arbiter of inter-elite disputes,” says Seva Gunitsky, a political scientist at the University of Toronto.

However, these political benefits may have come at a significant cost: military effectiveness. With all these divisions, it’s harder for the Russian military to operate as a united force in Ukraine. When commanders feud and disagree over objectives and the allocation of soldiers and materiel, the entire war effort suffers.

This is a well-documented problem. In her book The Dictator’s Army, Georgetown professor Caitlin Talmadge finds that authoritarian regimes worried about coups generally perform worse on the battlefield than those that aren’t, for exactly this reason. Coup-proofing is a good survival tactic in peacetime, but a recipe for defeat during war.

Putin’s paranoia about losing power is a major reason why he decided to invade Ukraine in the first place. It’s ironic that it may also be a major reason why he’s losing.

0 Comments