A new bill aims to curb conflicts of interest in Congress — but lawmakers could help themselves get around it.

Democrats have been working for months to nail down legislation that would make it harder for members of Congress to use information they receive on the job for their own financial gain, following a string of instances over the last few years in which they appear to have done just that. Recall 2020, for example, when Sens. Kelly Loeffler (R-GA) and David Perdue (R-GA) faced scrutiny for stock trades they made during the pandemic.

Those efforts have culminated in the release of the Combating Financial Conflicts of Interest in Government Act, a bill which prohibits Congress members, their spouses, and their dependent children from trading stocks. That ban would apply to the federal judiciary and high-ranking members of the executive branch as well as Congress.

Ethics experts warn, however, that there’s a risk a key provision in the bill could be exploited, diluting its impact.

Under the legislation, lawmakers would be required to either divest from their stock holdings or put them into a qualified blind trust, an entity run by an independent person, known as a trustee, who would be able to buy or sell stocks without their knowledge. The bill also requires that any existing stocks put into that trust are sold within 18 months of establishing it, so lawmakers don’t know what stocks are in it.

But as part of the bill, the House and the Senate would be able to set their own new definitions of what a “blind trust” is, a policy that could provide bad-faith actors an opening to make its requirements more flexible. Former Obama administration ethics chief Walter Shaub raised concerns about that in a Twitter thread Wednesday.

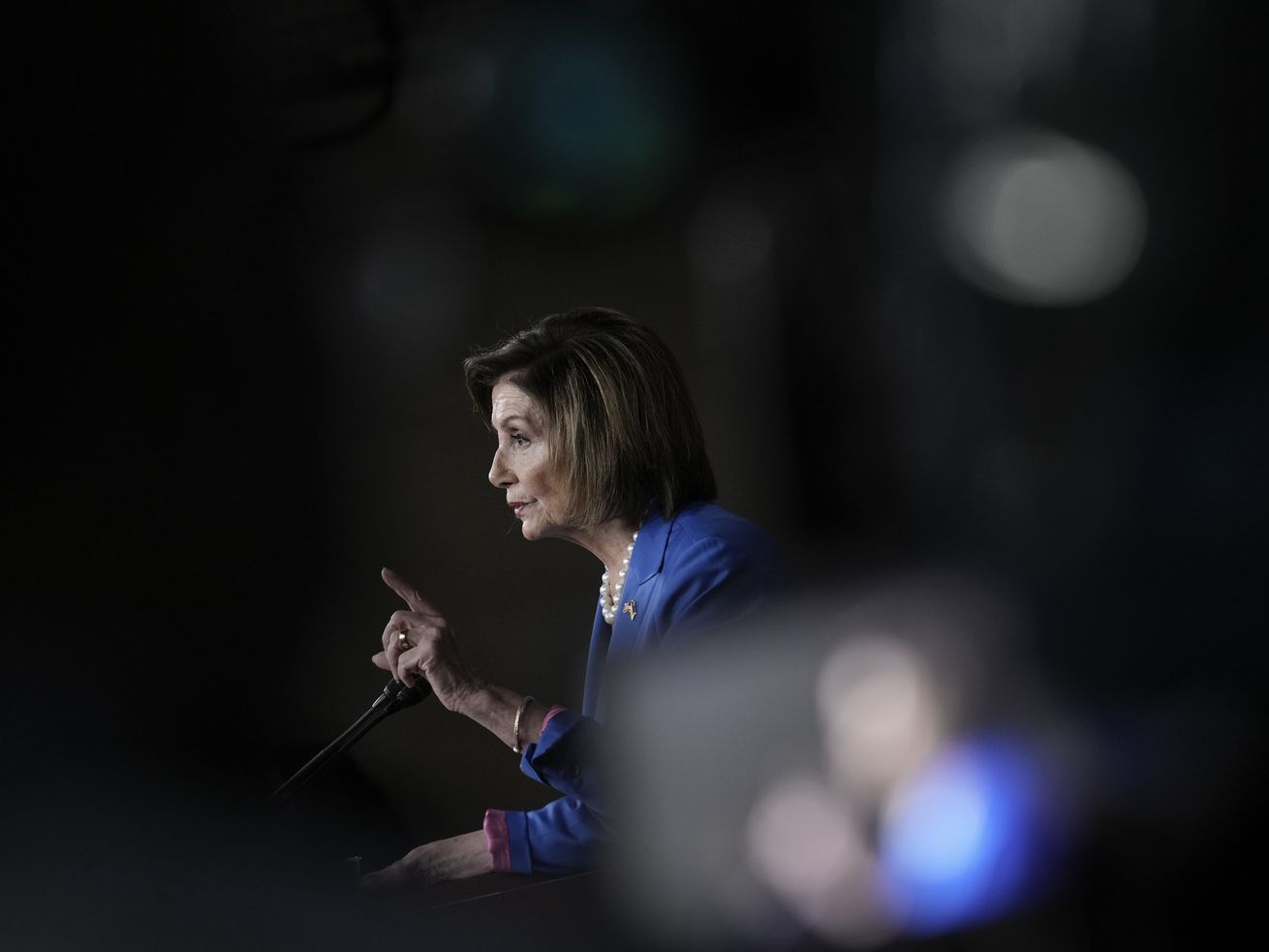

As drafted, the stock ban bill Pelosi introduced yesterday would destroy the federal government’s ethics program. It would be checkmate for ethics. And before you make the “there are no ethics” cracks, there in fact are, and this is like dropping an atomic bomb on them. https://t.co/Tg6mOGMNKR

— Walter Shaub (@waltshaub) September 28, 2022

A House Administration Committee aide pushed back on this characterization, telling Vox that the ability to set new definitions is needed to adapt to changes in the financial sector and allow lawmakers to modify the language over time.

Kedric Payne, the senior director of ethics at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonprofit government watchdog group, acknowledged both possibilities, noting that there was a small chance the bill could be abused. “From a good perspective, this provision was put in there simply to prepare for the unexpected,” Payne told Vox. “From the bad perspective, you think someone is putting in a trap door that allows too much flexibility in the law and a complete loophole.”

The potential loophole in the bill, briefly explained

The issue Shaub has raised with the bill centers on what constitutes a “blind trust.”

For a blind trust to work, lawmakers shouldn’t know anything about the stocks it contains, and they shouldn’t have a say in the purchases and sales that are made. As Shaub explained on Twitter, the existing requirements around a “blind trust” were established by an ethics bill in the 1970s, and were quite stringent.

Democrats’ new bill would give the House, Senate, the Supreme Court, the rest of the federal judiciary, and the executive branch’s ethics panels flexibility to determine what a “blind trust” is. That power, Shaub argues, could be used to set up what he describes as a “fake blind trust.”

“Pelosi’s bill would … [authorize] each ethics office to allow anything they want and call it a blind trust. Literally anything. There are no limits in the bill as to what these office can do,” Shaub wrote in a tweet.

Shaub’s reference point is the “fake blind trust” that former President Donald Trump set up, which included handing over control of his businesses to a council composed of his children and other executives in an attempt to suggest independence.

Were this tenet of the bill abused in a similar fashion, lawmakers could theoretically give themselves more visibility and input into the purchases and sales that are made in any trust, effectively defeating the purpose of the legislation.

Payne said this was a risk posed by the bill, though he felt there was a low likelihood that Congress would capitalize on it, and that there were easy fixes lawmakers could make to the bill to outline how strict the blind trust needed to be.

Another issue Payne raised, as did Shaub and the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), was the inclusion of the judicial and executive branches in the bill, both parts of the government which he said already had strong recusal policies in case there was a conflict of interest. Shaub has suggested that the inclusion of these two branches is intentional to reduce the Senate support the bill could have.

The House aide argued, however, that ethics rules have typically been applied across all three branches and that the bill would only strengthen existing policies.

How the bill would address conflicts of interest

The stock trading bill is the result of renewed scrutiny of Congress, and lawmakers’ use of information they learn at work to bolster their own personal profits.

A 2022 Business Insider investigation found that 72 members of Congress had violated the STOCK Act, which requires lawmakers to disclose stock trades they make and prohibits them from using confidential information for their own financial transactions. Enforcement of that bill has long been meager, an issue that Democrats’ new proposal tries to take on as well. Under the new bill, lawmakers would also still be able to invest in diversified mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs), and government bonds.

Stock trades by Loeffler and Perdue, as well as Sen. Richard Burr, are among those that have prompted more recent attention on Congress. At the start of the pandemic, Loeffler had made millions worth of trades after attending a briefing on the coronavirus, raising questions about whether these trades were informed by that meeting.

At this point, there’s still uncertainty about whether the bill has the votes to pass the House, where some Democrats have been resistant to legislation on the issue because they think it’s unnecessary. Recently, Punchbowl News reported that House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer is among the lawmakers who have signaled opposition to the bill, a position that could spur other Democrats to defect as well. A spokesperson for Hoyer has said he’s still reviewing the text of the legislation, which was released on Tuesday.

House Democrats had originally intended to vote for a bill overseeing lawmakers’ stock trades before they left for an October recess ahead of the midterms, but internal disagreements on the subject could mean that it gets punted to the lame duck session after that. Because of their narrow majority — and the likely lack of Republican support — Democrats can’t afford to lose more than a handful of lawmakers to pass the bill.

Senators have also said they won’t put forth any stock trading legislation until after the midterms. In both chambers, proponents of the bill have stressed that it’s vital for Congress to hold itself accountable, and give itself the same oversight as other industries.

0 Comments