We have safe, effective options — but in short supply.

The worldwide monkeypox outbreak that began in early May has so far led to more than 7,500 infections in 57 countries, with more than 600 of them in the US. Behavioral strategies are critical for preventing monkeypox transmission — check out the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) refreshingly straightforward advice about cleaning fetish gear! — but with case counts still rising, vaccination against the virus is more urgently emerging as an important tactic for stopping its spread.

Monkeypox generally causes several days of flu-like illness and lymph node swelling followed by a blister- or pimple-like rash. While the version of the virus causing the current outbreak is rarely lethal, its lesions can be extremely painful and may leave scars.

Public health authorities have been administering vaccines to close contacts of monkeypox cases since the early days of the outbreak. But in recent weeks, they’ve been taking a more expansive approach to vaccination, offering it to people at risk for monkeypox exposure — even if they haven’t had contact with a confirmed case.

In June, community-based vaccination clinics began popping up in Canada, Europe, and the US. But demand has greatly outpaced supply, especially in American settings, leading to confusion and frustration among people seeking vaccination.

The monkeypox landscape is changing fast. Here’s what you need to know about the vaccine, whether you’re considering getting one yourself or just trying to make sense of it all.

What vaccines are available to prevent monkeypox, and how do they work?

Two vaccines are currently approved for use against monkeypox in the US, but it’s not because of monkeypox that we have them.

Let’s back up: Until the late 1900s, smallpox was a global scourge. For at least 12,000 years, it decimated populations and felled entire empires, killing about a third of the people it infected. The virus was eradicated worldwide in 1980, but because it is such a potent killer, experts still considered the smallpox virus to be a serious threat for use as a weapon. “The only reason we have the smallpox vaccine is because it’s a bioterrorist threat,” said Isaac Bogoch, an infectious diseases doctor at the University of Toronto. For that reason, many countries keep a modest quantity of smallpox vaccines in their national stockpiles, and for the same reason, they may be cagey about the exact size of their supplies.

Smallpox was eradicated with the help of Dryvax, a live virus vaccine made using a smallpox relative called vaccinia. Although it was effective, Dryvax had some nasty side effects, and in 2007 it was replaced by a safer and equally effective alternative called ACAM2000, which had good protective effects not only against smallpox but also against monkeypox and other related viruses. Still, the live virus in ACAM2000 could reproduce inside human cells, and nearly 1 in 175 people who received the vaccine developed an inflammatory heart condition called myocarditis (treatable and not usually lethal, but still, not great to have).

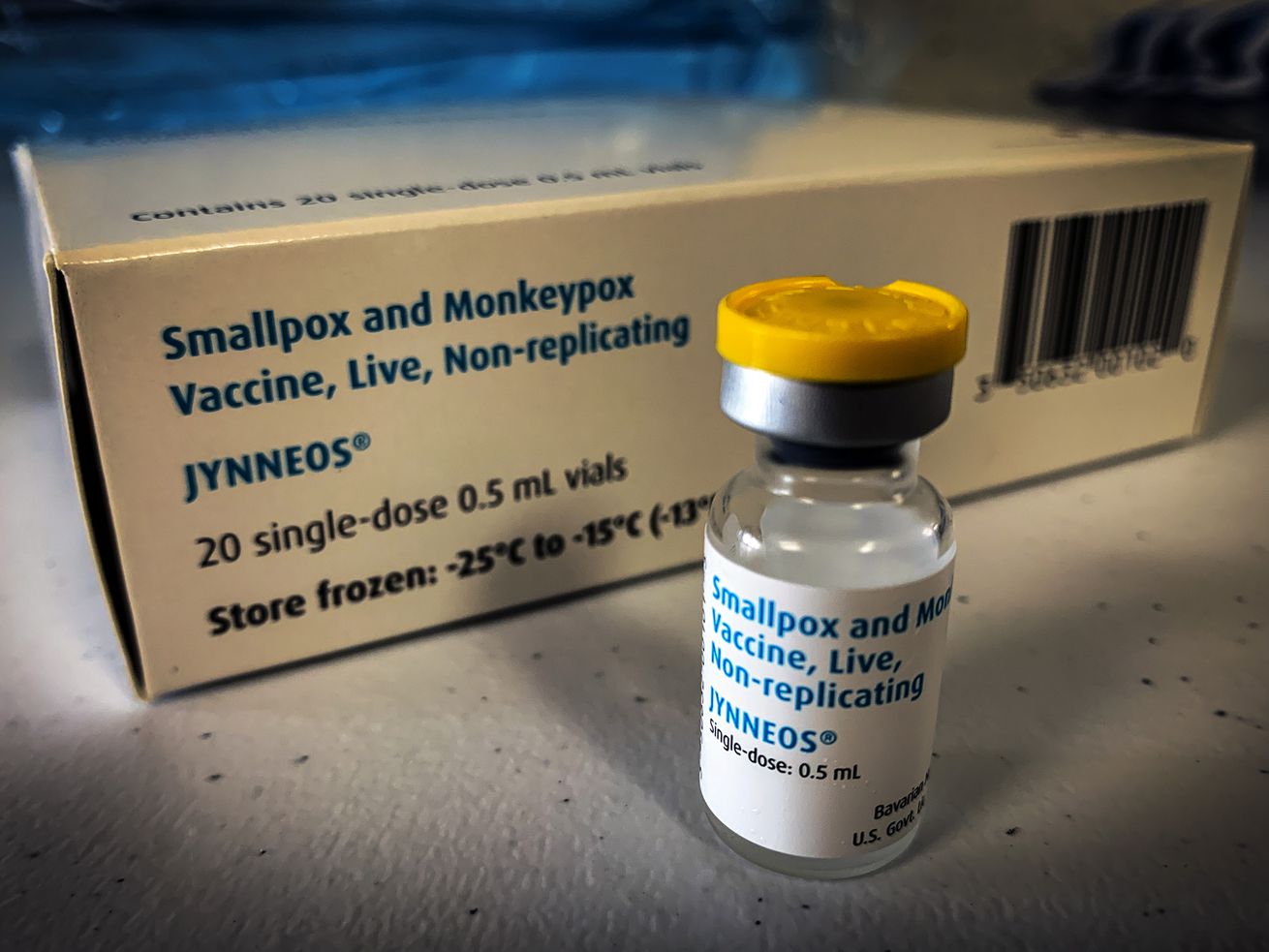

In 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration approved another vaccine for both smallpox and monkeypox. This vaccine was made using a live virus — modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) — that elicited a potent protective response without being able to reproduce in human cells. As a result, these MVA vaccines had far fewer side effects than ACAM2000.

The US federal government has kept both vaccines in its strategic national stockpile for the last few years, but has far more of the older vaccine: As of late June, the US had about 65,000 doses of the MVA vaccine (branded as “Jynneos” in the US) and more than 100 million ACAM2000 doses.

Many people born outside the US prior to 1980 — and many who lived in the US before 1972 — have been vaccinated against smallpox. Those vaccines also made them immune to monkeypox and other viruses related to smallpox, called orthopox viruses.

For decades, that immunity kept viruses like monkeypox at bay. However, as immune people have aged or died and new, unvaccinated people have been added to the population, waning population immunity has recently opened the door to increasing numbers of monkeypox infections. That dynamic explains why Nigeria — and now the world — has been seeing more of these infections in recent times.

When is monkeypox vaccination most protective?

A helpful feature of both monkeypox vaccines is that they can prevent disease in people even if they receive it after being exposed — that is, as “post-exposure prophylaxis.” According to the CDC, receiving a vaccine up to four days after exposure can prevent disease onset altogether, but even getting it up to two weeks after exposure can reduce symptoms. (Several other vaccines also have this feature, among them vaccines for rabies and hepatitis A.)

The complete regimen of both vaccines has generally included two doses given two or four weeks apart. And while experts suggest only one dose of an MVA vaccine may be adequate to prevent monkeypox in the current outbreak setting, the US is still using two-dose regimens because that’s what the US Food and Drug Administration has approved.

It’s still best to get vaccinated before being exposed because levels of the protective antibodies we make in response to MVA vaccines like Jynneos peak about a month after starting the two-dose series.

Although it would be ideal to get everyone at risk vaccinated before they’re exposed, “you need a lot of things to go right to roll that out,” said Bogoch. No part of the public health response is in isolation: For a vaccine program to work smoothly, communities and health care providers need to be aware of it, and barriers to vaccination need to be as low as possible. There’s still a lot of work to do before the people most at risk can easily get vaccines.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23754118/1241489701.jpg) Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Who should get vaccinated for monkeypox?

Because the vaccine supply is relatively low in the US, there’s a big difference between who should get vaccinated and who can get vaccinated.

Most people involved in the current outbreak have been gay and bisexual men, many of whom reported recently having multiple or anonymous sex partners. For that reason, vaccination strategies and other preventive activities have been focused on these groups.

Generally, people eligible for vaccination fall into one of three categories: known contacts of people with monkeypox infections, people whose sex partners in the last 14 days were diagnosed with monkeypox, and people with multiple sexual partners in the past 14 days living in an area with known monkeypox cases. (Although these criteria are set by the jurisdictions administering the vaccine, they’re often similar because they’re based on guidance from the CDC.)

The first group — known contacts of cases — have generally been able to access vaccines. Public health authorities often identify people in this group during contact tracing or similar activities, and offer vaccination to help prevent disease and transmission.

However, people in the other two groups have had a harder time getting vaccinated, despite their elevated risk for exposure. The company that makes the Jynneos vaccine has expressed confidence it can scale up to meet demand, and as vaccine supply improves, so should vaccine access.

People who were vaccinated against smallpox during eradication campaigns of the mid- and late-1900s — most of whom are over 40 — retain lifelong immunity against related viruses and do not need to be re-vaccinated to get protection from monkeypox.

What’s the US supply of monkeypox vaccine?

Vaccine supply to states and cities began as a trickle during the early days of the outbreak, mostly for people exposed to confirmed cases. By the end of June, only 9,000 vaccine doses in total had been distributed for this use.

In mid-June, some states began getting bigger vaccine allocations for use in larger groups of people. On June 23, the New York City health department began offering vaccination to men with multiple or anonymous sex partners in the prior two weeks, and the Washington, DC, health department did the same on June 27. Both ran out of vaccine almost immediately, as did health departments in San Francisco and Atlanta.

On June 28, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that a big vaccination push was coming. Throughout July, the agency said, it would supply 296,000 more doses of vaccine to states, 56,000 of them immediately. Additionally, the US government has bought an additional 500,000 existing doses and ordered another 2.5 million doses yet to be packaged. The agency said it expects 1.6 million of those doses to arrive in the US before the end of 2022, with the remainder expected in early 2023.

As of early July, the US government had distributed 41,520 doses of vaccine to US jurisdictions.

What’s the best way for people who want a monkeypox vaccine to get one?

For now, state and local health departments are in charge of vaccinating their communities. Most jurisdictions in the US do not currently have enough supply to meet demand. However, HHS announced on July 7 that it planned to ship an additional 144,000 doses to health departments on July 11 — and if things go according to plan, more supply will soon follow.

The people who stand to benefit the most from monkeypox vaccines are gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, especially if they have lots of sex partners or anonymous partners. And the health departments most likely to have or get vaccines are those in places that have had a lot of monkeypox cases (with the notable exception of Florida, which has reported about half as many cases as California but has received one-twentieth the number of vaccines).

Currently, the best way to determine whether you can get a vaccine is to Google your nearest health department — it might include the name of your city or county — and reach out to them. Some, like the New York City and Washington, DC, health departments, have websites you can monitor, where you can sign up when appointments become available. But honestly, it’s a patchwork: While the Colorado health department offers residents a Google form, neither the Chicago city government site nor its Cook County health department offers any information about vaccine availability.

As with Covid-19 vaccines, our federalized public health system leaves the distribution of monkeypox vaccines to depleted and underfunded state and local agencies, and the piecemeal availability reflects that.

Why is it taking so long to get vaccines to the people who want them?

Public health authorities and health advocates say limited resources and problems at US government agencies are at the root of the delays.

David Holland, an infectious disease doctor and chief clinical officer at the Fulton County Board of Health in Atlanta, tweeted his frustration with the limited resources available to support a local vaccination program. “Not in our budget, and we don’t have the staff to do this,” he wrote.

Monkeypox testing & PEP vaccines are increasing exponentially. Not in our budget, and we don’t have the staff to do this plus our regular sexual health stuff.

— David Holland, MD, MHS (@DavidHollandMD) July 6, 2022

Did anyone consider this when deciding to sit on vaccines for over a month?

Do we still not understand exponents?

James Krellenstein, who directs strategy and policy at Prep4All, an organization that advocates for improved access to lifesaving medications, said the lag is a consequence of poor planning by US government agencies. In a letter addressed to White House officials, Krellenstein and a co-author wrote that a million already-purchased Jynneos doses are stuck in a freezer in Denmark because the Food and Drug Administration neglected to inspect the production facility in a timely manner.

“This should have been a hole in one,” Krellenstein said in an interview, because monkeypox is a disease for which we have stockpiles of FDA-approved vaccines and medications. “Despite all those advantages, we are fumbling in the dark.”

What does an ideal monkeypox vaccination strategy look like?

People might wonder why we don’t just go back to vaccinating everyone for smallpox again — after all, we never had to worry about monkeypox back when smallpox vaccination was routine. A global vaccine campaign aimed at reinstating widespread immunity to orthopox viruses (the family that includes smallpox and monkeypox) would certainly prevent monkeypox virus outbreaks, but most public health experts agree that kind of a campaign isn’t practical or cost-effective. “It’s premature,” said Bogoch. “The risk to the general public right now, at least in the United States, is negligible.”

Instead, public health authorities favor monkeypox vaccination strategies that focus on either vaccinating close contacts of known cases (a strategy sometimes called “ring vaccination”) or by vaccinating all members of groups who likely have been or could be exposed to the virus.

An ideal monkeypox vaccination program would have three important components, said Krellenstein. The first is a robust supply of vaccine. “There is no better friend of structural inequities in the United States health care system than scarcity,” he said, and ensuring a plentiful vaccine supply would help avoid a situation where only those with access, power, and money get vaccinated.

In the case of monkeypox, creating vaccine administration sites outside of traditional health care contexts is also critically important, said Krellenstein. “We need to get them into bathhouses, into community centers, into pharmacies, into physicians’ offices,” he said, “into places where people who are vulnerable actually are meeting and congregating.” Such strategies have in the past been instrumental in ending meningitis outbreaks among communities of gay and bisexual men.

The third important pillar in a successful monkeypox vaccination program is funding, said Krellenstein. Vaccines don’t save lives without the programs and messaging that get them into the people who need them, he said — and there’s no indication that funding is on the way in the US.

0 Comments