The president says reducing the deficit will lower inflation. Will it?

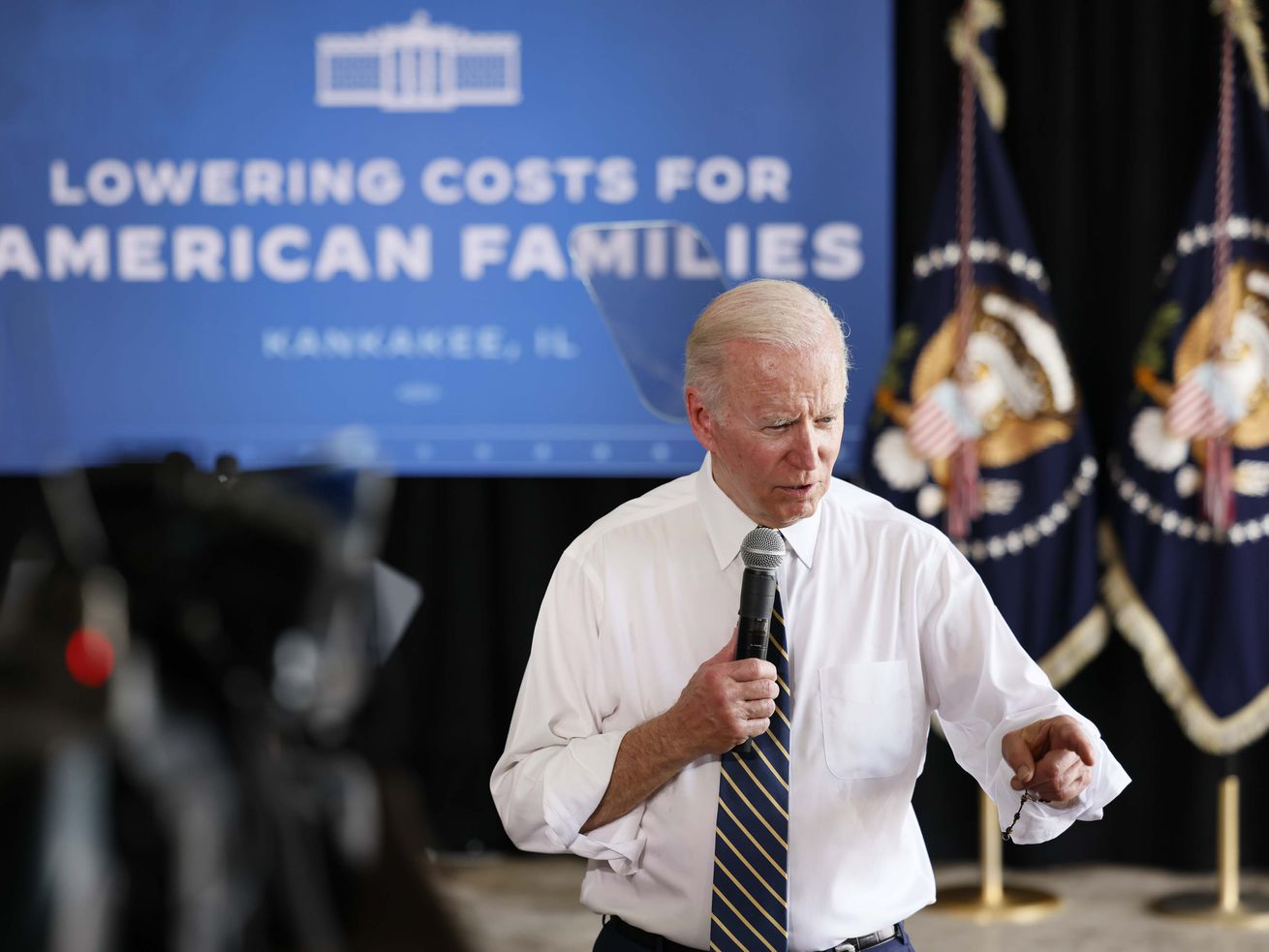

Fuel prices are rising, rent is too damn high, and elections are coming. As inflation and high costs of living spoil the country’s economic mood, President Joe Biden has revived a recent talking point to get across how seriously he takes the country’s economic situation: “I reduced the federal deficit.”

Cutting government spending isn’t really top of mind for most American voters, and balancing federal budgets is certainly not going to be enough to motivate Democratic voters to turn out in midterm elections. The federal budget deficit hardly registers in Gallup’s recent polling on the country’s most pressing problem, but inflation is at the top of the list.

With midterms coming up and a new inflation estimate scheduled to be released next week, the White House is now making deficit reduction a core part of its intense efforts this month to convince voters the economy is getting better — and reset public opinion on its biggest political challenge.

It marks a pivot: Biden campaigned on wanting to be a transformative president, pushed for massive spending packages throughout 2021, and played down concerns of inflation to boost those proposals. But the president now sounds more cautious about big government spending.

That pivot started at his state of the Union speech earlier this year. “My plan to fight inflation will lower your costs and lower the deficit,” he said in March. “By the end of this year, the deficit will be down to less than half what it was before I took office.”

Inflation has gotten steadily worse and stayed high since then, but the White House’s messaging on the problem really kicked into overdrive in recent days. Biden rolled out a three-pronged approach — one being deficit reduction — to wrangle inflation in a Wall Street journal op-ed. He’s also invoking the deficit in speeches, and addressed the country about it again on Friday. His administration’s officials popped up on television screens this week to talk about the plan, and the White House is planning more announcements, interviews, and trips for the rest of the month.

Biden’s claim that his policies are responsible for the drop in the spending gap are debatable. But even if they were completely true, it’s not totally clear that cutting back federal spending would, at this point, help bring down inflation, according to economists. Whether it convinces the average American is even more dubious. But the administration is going to try.

A refresher on the deficit, and Biden’s role in getting it down

The federal deficit is the amount of money the federal government spends in a year’s budget beyond what it has collected in revenue. That shortfall gets added to the country’s total debt. The United States has run up a budget deficit every year since at least the early 1970s, except for four years between 1998 and 2002.

It ran its largest deficits ever during the core pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 because of emergency coronavirus spending through the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan. Because that funding is winding down or all spent, and because tax revenues have increased as unemployment dropped and the nation’s overall economic recovery sped up over the last year, the deficit dropped in 2021. An even bigger drop is projected by the end of the 2022 fiscal year in September.

Over the last few months, Biden has taken credit for this drop in the deficit in his State of the Union address, in speeches throughout April and last month, when he sought to “remind you again: I reduced the federal deficit” despite “all the talk about the deficit from my Republican friends.”

Focusing on the deficit is traditionally much more of a priority for Republicans than Democrats. You tend to hear about it from congressional Republicans who want to cut back on social welfare spending or attack Democrats for spending at all. Many words have been written about just how much deficits matter, but economists who spoke to Vox said that they matter more in times of high inflation.

It’s true that deficits are decreasing: The $2.8 trillion deficit in 2021 was lower than the record $3.1 trillion deficit from 2020, when Donald Trump was president. And the projected 2022 deficit of $1 trillion will be an even steeper fall — something for which the president is taking credit. But that’s largely a product of the big spending programs from 2020 and 2021 tapping out, according to many economic experts. Biden’s signature spending package, the American Rescue Plan, worsened the deficit to a degree — shrinking a projected $870 billion deficit reduction to the $360 billion decline that actually happened from 2021 to 2022.

“I’ve heard the president and his administration say over and over again, things like ‘we have reduced the deficit because of our actions.’ That is only true in a very backward sense,” Marc Goldwein, a senior vice president at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a fiscally conservative group, told Vox. “The deficit is coming down year over year overall despite their actions.”

It’s also true that American unemployment has been dropping quickly over the last two years — meaning more people are paying taxes that help offset government spending. On that front, the White House credits its recovery efforts.

The effects of deficits on inflation are debatable

Even if Biden gets full credit for bringing down the deficit, casting it as a tool to fight the country’s current level of inflation is a new approach for him. “Bringing down the deficit is one way to ease inflationary pressures,” he said in early May. “We reduce federal borrowing and we help combat inflation.”

Economists don’t all agree on just how much taxing and spending can do to combat inflation.

“Not all government spending is clearly inflationary,” Goldwein said. “But when you’re in a period of high inflation, you can probably expect the first-order effect of any given increase in spending or any given cut in taxes is probably going to be inflationary.”

Big deficits can certainly worsen the problem if that’s the result of a massive injection of money into the economy when the economy is overheated, but the primary responsibility for controlling inflation falls on the Federal Reserve, which controls interest rates and money supply — and the White House is emphasizing that point in its economic plan: “My predecessor demeaned the Fed, and past presidents have sought to influence its decisions inappropriately during periods of elevated inflation. I won’t do this,” Biden wrote in an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal this week.

Biden acknowledges he has more control over how much revenue the government can collect in taxes and how much it chooses to spend. “Because government is such a large purchaser, and because it’s such a big part of our economy, if you lower the amount of deficit — so you either increase taxes or you lower spending — you’re going to pull some money out of the economy, and that can reduce inflationary pressures,” a senior administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Vox about the White House’s thinking on the deficit-inflation link.

But there’s a difference between simply not worsening inflation by growing deficits and taking active steps to reduce the deficit. By not increasing spending on policies that put more money in people’s hands, the government can try to hamper demand for goods and services. There’s still plenty of money out in savings accounts and the coffers of state and local governments that will make this a challenge — and supply chain and logistics concerns that can’t just be solved by cutting spending and raising taxes — but the White House is suggesting a handful of reforms in a renewed economic message it is rolling out this month.

The president isn’t expecting any more big immediate spending, but knowing that the government can fight inflation on the margins through long-term investments and tempering expectations about future economic growth, Biden’s plan has a shot at making things feel better.

Biden’s new economic sprint

In his Wall Street Journal op-ed, Biden laid out an inflation-fighting plan to ease the country into “stable, steady growth” that includes deficit reduction as just one of three planks; letting the Fed do its work and making things more affordable are the other two. He expanded on this message during an address Friday focused on the May jobs report that shows hiring still rising and unemployment remaining near a pre-pandemic low.

He wants Congress to reform the way the IRS collects taxes from regular Americans and how billionaires and corporations pay taxes, as a way to not just reduce the deficit even more, but fight inflation by punishing price-gouging and “corporate greed.” White House officials this week have also made television appearances and public statements to push this new message and announce infrastructure and climate investments to improve supply chains.

These new moves are happening as inflation remains near a record high, gas prices soar as summer travel picks up and energy markets remain chaotic after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the outlook for Democrats in midterm elections worsens.

Many of Biden’s proposed fixes require congressional action — something Biden is eager to emphasize: “I’m doing everything I can on my own to help working families during this stretch of higher prices. And I’m going to continue to do that,” he said on Friday. “But Congress needs to act as well.”

As part of this larger strategy, the White House seems to be gearing this deficit message toward the most fiscally conservative members of his caucus in Congress: Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona have been frequent obstacles to Democrats’ ability to pass any new economic plans through the Senate, and both have signaled their concern over worsening inflation.

Whatever reforms and proposals could make it through the House and Senate would have to satiate those concerns, and so far, Biden’s plan is straddling that line by increasing revenue and investing in longer-term economic productivity and cheaper energy production, which some economists say can help alleviate longer-term inflationary pressures.

This deficit and inflation pivot is also a test of a traditional presidential power that has been waning in recent administrations: the bully pulpit, or the president’s influence to set agendas, dominate national conversations, and persuade other politicians to fall in line. Biden has reportedly been frustrated by his inability to break through to the general public and craft a cohesive message on the many challenges his administration is trying to tackle, from inflation and gas prices to gun violence and the pandemic.

On Friday, he tried to explain his focus on affordability and reducing the deficit in terms Americans might understand, “I understand that families who are struggling probably don’t care why the prices are up. They just want them to go down. … But it’s important that we understand the root of the problem so we can take steps to solve it.” he said. “The reason this matters to families is because reducing the deficit is another way to ease inflation.”

Presidents have seen this power of persuasion eroded as party polarization increases, Congress gets harder to unify, and messaging power is diffused among media, political organizations, and activist groups. For Biden, part of the problem comes from his tendency to misspeak or have his comments corrected or cleaned up by staff afterward. But the senior administration official who spoke to Vox argued it’s worth Biden making this outreach: “The president is trying to help people understand the role that this democratically elected government can play in people’s lives to help improve economic outcomes, and then by that, help to improve people’s outcomes.”

We will see in a few months whether this posturing convinces any voters. But by at least speaking about it and laying out a plan, the White House can counter Republican attacks about wasteful government spending and irresponsible government borrowing and message to average Americans that it is being responsible with its spending just like Americans who are concerned about affordability.

Still, for the strategy to succeed, it will have to break through to average Americans who may not know what the deficit is, but do know that the price of gas and food is rising. Whether that happens on television or in person (the White House is hinting at future trips and speeches), the message has to get out there. And as part of a larger plan, it may address the general confusion and malaise so many Americans are feeling.

0 Comments