Batuman’s second novel is shaggy, strange, and sweet.

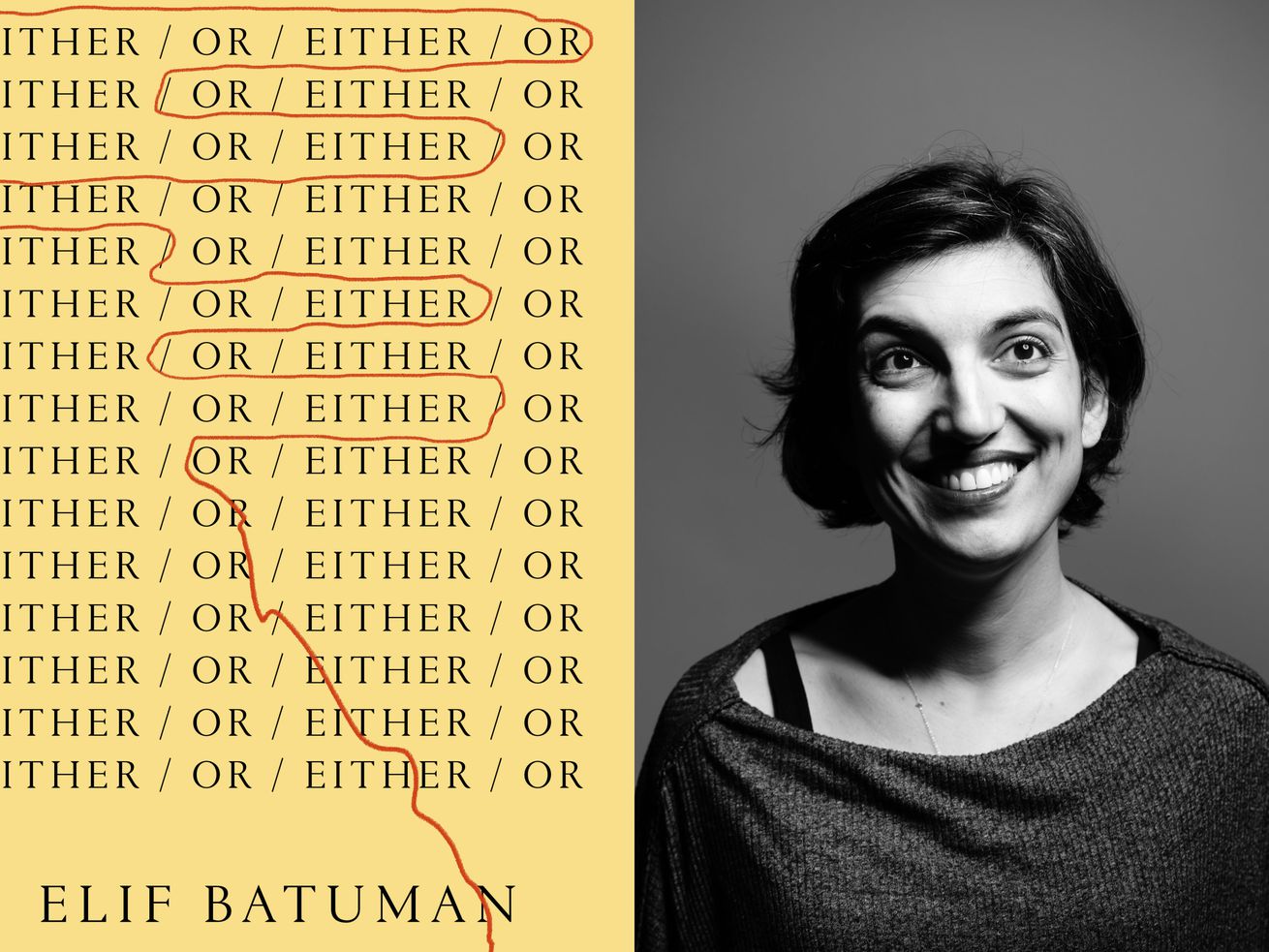

The Idiot, Elif Batuman’s charmingly deadpan debut novel of 2018, was unconventional as coming of age stories go. The protagonist, Selin, took very few concrete actions, and at the end she informed us that she “hadn’t learned anything at all.” Either/Or, Batuman’s follow-up to The Idiot and a direct sequel, shares its predecessor’s dryly understated wit, but it does so with a far more conventional structure. By the end of Either/Or, Selin has definitely learned something.

Selin is an undergraduate at Harvard in the 1990s, just as email is beginning to become A Thing. In The Idiot, she carried out a flirtation with an enigmatic Hungarian mathematician named Ivan almost entirely by email, all the while studying linguistics and thinking very hard about the relationship between language and meaning. When she followed Ivan to Hungary at the end of her freshman year, though, their relationship ended without so much as a kiss. All that harping on language in her classes and emails hadn’t helped her much at all once she tried to take her love story out into the real world.

Now, as Either/Or begins, Selin steps into her sophomore year determined to take on a new outlook on life. She’s switched her major from linguistics to literature, and having decided she wants to be a novelist, she commits herself to learning how to live an aesthetic life. The trouble is, she’s not quite sure how to go about doing such a thing.

Søren Kierkegaard’s philosophical treatise Either/Or, which Selin encounters early on in the novel and which gives this volume its title, presents the aesthetic life as the counterpart to the ethical life of marriage and children. (The Idiot was named after the Fyodor Dostoevsky novel of the same name, and Batuman’s 2010 memoir The Possessed also took its title from Dostoevsky.) Selin, who has no interest in either marrying or having kids, pounces on it eagerly, but she’s disappointed to find that Kierkegaard’s version of the aesthetic life mostly revolves around seducing and then abandoning young women. When Selin reads his account, she recognizes herself not in the seducing aesthete but in his victim, the heartbroken Cordelia.

“Was there a way of viewing Cordelia’s situation as not bad, or as bad for only historically contingent reasons?” Selin wonders with a hint of desperation. “Was there a version of ‘The Seducer’s Diary’ where they were equal?”

Lacking a clear map forward from one of her textbooks, Selin is left to improvise as best she can. She signs up for a class on chance. She experiments with making only the decisions she would want a character in a novel to make, on the grounds that at a certain point, she can just write down everything that happens to her and that will be a book. And she decides, with a little less remove than perhaps she would like to suggest, to lose her virginity.

It’s that slipping clinical mask that separates Either/Or most definitively from The Idiot. Selin is by nature a character who spends most of her time thinking, and in The Idiot, she was able to use those thoughts to successfully distance both herself and the reader from her emotions, particularly the more bodily ones. It was clear that she was spending a great deal of time thinking about Ivan, but Selin wasn’t about to tell us that she thought about having sex with him.

But seven pages into Either/Or, Selin informs us that while the thought of having sex with Ivan or anyone else doesn’t seem that appealing to her, sometime off the page in the previous book, she had considered what it would be like to do the deed. Moreover, “it was immediately obvious that if Ivan tried to have sex with me, I would let him.” The Selin of The Idiot would have died before admitting as much to us.

Because Selin spends less time in Either/Or hiding from her feelings than she did in The Idiot, this novel has less of its predecessor’s cool polish. This book is shaggier and less disciplined, but also more vigorous, and Selin has become a stronger and more definite character. When she chooses to veil her emotions, it is only to make the inevitable unveiling all the more devastating.

Her eventual and catastrophic first time, she glosses over in an understated blood-streaked montage, capped off with what she considers “a really funny joke”: “So this is what the big deal is about?” she says brightly to her panicked paramour (he does not laugh). But 20 pages later, Selin goes back over the event with an unexpectedly brutal summation: “I had been hurt, and hurt, and hurt, for two hours,” she tells us. The line lands like a blow.

Selin’s romantic travails, though, exist in service to a greater quest: her twin attempts to figure out how to be a writer and how to live the kind of life she considers worthwhile. On this subject Batuman’s prose turns tender, and the wryness of her humor becomes affectionate. Selin cultivates an end-of-history apoliticism and never identifies as a feminist within the text, but she can’t help but notice that a lot of the books she admires are written by men about women they consider stupid. Figuring out how to become a good writer, like figuring out how to live an aesthetic life, means finding a way to not quite identify with either. By the end of Either/Or, Selin has at last amassed enough confidence to see her way forward.

“I wasn’t dumb or banal, and I lived in the future,” Selin concludes from the comfort of the 1990s. “Nobody was going to trick me into marrying some loser, and even if they did, I would write the goddamn book myself.”

Do you pick the aesthetic life or the ethical life? If you’re Selin, you pick the aesthetic life — but you’re in charge of what the aesthetic means.

0 Comments